She is the most listened-to French singer in the world, whose relentlessly catchy hits about love and betrayal have been streamed 7bn times and who made history last year when she sold out three Paris gigs in 15 minutes.

But Aya Nakamura, France’s biggest pop superstar who is known for her unique French style influenced by Afrobeats and Caribbean zouk, called out racism and ignorance this week after far-right politicians expressed outrage over the possibility that she could sing at the Paris Olympics.

The Paris prosecutor opened an investigation on Friday into alleged racist abuse against the singer during the Olympics row. A complaint had been filed by the France-based International League against Racism and Antisemitism.

Emmanuel Macron is yet to confirm that he wanted Nakamura to headline the Olympic opening ceremony, singing hits by the 1950s cabaret legend Édith Piaf. But complaints by rightwing politicians and TV pundits that Nakamura was somehow not French enough have exposed deep faultlines of racism and class prejudice that threaten to cast a shadow over the Games.

Rachida Dati, the culture minister, warned against “pure racism”, and Lilian Thuram the former French footballer said: “When people say Aya Nakamura can’t represent France, what criteria do they base it on? I know the criteria, because when I was a footballer, some also said this isn’t the French team because there are too many Blacks.”

Nakamura, 28, grew up on a housing estate in the northern Paris banlieue suburbs of Seine-Saint-Denis, exactly the communities that the Paris Olympics has promised to showcase and celebrate. Born Aya Danioko in Mali, she arrived in France as a baby. She lived in Aulnay-sous-Bois with her siblings and mother who was a griotte, a traditional Malian poet or singer. She took the stage name Nakamura from the superhero drama Heroes and was talent-spotted after posting songs online aged 19. Her unflinching lyrics on love and relationships, which she writes on her phone, quickly gathered a huge following.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

French music critics argue that no other female singer in French history – not even Piaf in her postwar stardom – has had Nakamura’s global reach, with fans on every continent, across all classes, backgrounds, ages. Her best-known song, Djajda, has had close to a billion streams on YouTube alone. Her music is resolutely French, influenced by French-Caribbean zouk pop from Guadeloupe and Martinique, mixing in Afropop beats. But while some big French export bands, such as Daft Punk, preferred to sing in English, Nakamura has built a huge global fanbase singing in French.

When politicians, including the rightwing senate leader, Gérard Larcher, this week attacked Nakamura for poor French because she used slang, other singers shot back that she was part of a long tradition of artists playing on the French language, from the poet Baudelaire to the musician Serge Gainsbourg. The singer Princess Erika said: “These people saying she doesn’t speak French, where do they live? Because Aya speaks not just a poetic French, but the French of young people.” Nakamura told a TV show last year: “There are so many people who speak like me, and there are young people who understand me.”

Mekolo Biligui, a rap journalist, said: “This row says a lot about what racism is in France. It’s not the first polemic of its kind. When the rapper Youssoupha was chosen by the French football team to record their anthem for the Euro 2021, there was a polemic by the far right. When the rapper Black M was due to perform at the centenary of the battle of Verdun, there was a polemic fed by the right. It’s starting to be a long list. What these performers have in common is they are Black. In France, there is a problem with Black artists. For a long time, France knew how to hide its racism. Here the country can no longer hide it.”

She said that on TV debates this week, Nakamura, a pop singer, was being wrongly labelled a rapper just because she was Black.

“My measure of how popular an artist is in France is when they start being played at weddings,” Biligui said. “You hear Nakamura played absolutely everywhere, particularly at weddings because she is so popular, she is the soundtrack to all parts of people’s lives … There is a classist element to criticising her French just because she includes slang. The vivacity of the French language is that it has always contained a lot of slang, from different towns and regions, north and south, and particularly in the melting pot of Paris … This row is trying to reduce Nakamura to the fact she comes from a working-class neighbourhood and is of African heritage. But in fact she’s totally of her time and absolutely part of French culture: she is influenced by zouk, Afro-Caribbean pop music from Martinique and Guadeloupe, which is France. Her music is 100% French.”

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

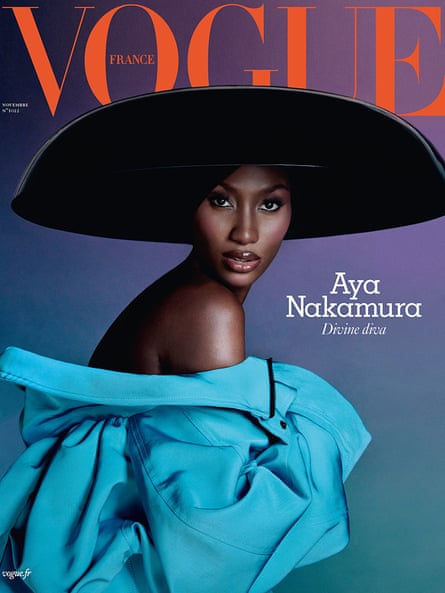

Christelle Bakima Poundza, is an author and critic whose recent book, Corps Noirs, on Black women in French fashion, examined how Nakamura’s award-winning, bestselling cover of French Vogue in 2021 was a first for a French Black artist. She cautioned that the Vogue cover came relatively late in Nakamura’s career, and she had had far fewer magazine covers in France than other white singers, despite selling millions of records.

Bakima Poundza, who last year hosted the first gathering of cultural criticism on Nakamura, welcomed a potential Olympics performance and felt the political class had been too slow to stand up for Nakamura against the far right: “She is the first artist who really represents everyone, listened to by all generations – the only artist who could allow France to present an open, diverse, generous and multicultural image. And yet France can’t even defend that image at home.”

Bakima Poundza saw the row over Nakamura as the latest attack on visible Black women in France, from abuse of the former justice minister Christiane Taubira when she spearheaded the same-sex marriage law in 2013, to the politician Rachel Keke in 2022. She said it added to the sense of a “hostile climate” for French people of colour, after a year in which there was unrest over the police shooting of a 17-year-old boy, Nahel, of Algerian descent, and a hardline immigration bill. She said it sent a message to others: “Don’t exist or represent France, or this is what will happen to you: harassment.”

It is still uncertain whether Nakamura will perform at the Olympics, but the Paris organising committee is trying to limit the damage from the row. “We are very shocked by the racist attacks against Aya Nakamura,” it said. “Total support to the most listened-to French artist in the world.”

∎