Parvati Shallow navigates social interactions the way Michael Phelps navigates a 50-meter swimming pool: smoothly, gracefully and with devastating efficiency. “I can connect with people and build trust and rapport very quickly,” she says.

It’s no idle claim. This skill set has made Shallow, 41, a reality television icon. Over the past 18 years, she has charmed, plotted, seduced, deceived and cajoled her way through four seasons of Survivor and the just-concluded US season of The Traitors, Peacock’s popular show where reality stars have to figure out who among them is trying to betray the group for prize money.

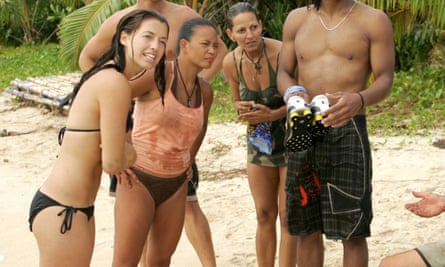

The public first met Shallow in 2006, on season 13 of Survivor, the long-running reality competition show. A 23-year-old University of Georgia grad with a thermonuclear smile and abs as hard as coconut shells, she made a name for herself on the season as a flirt, using her preternatural charm to secure allegiances and dodge elimination.

Shallow didn’t win, but she made it pretty far. Three seasons later, she returned to Survivor older (26) and wiser (she was still going to flirt, she said, but more strategically). She pulled together an all-female alliance that ruthlessly mowed over the male contestants, and in the end, she won the $1m prize pot.

On the second US season of The Traitors, she was recruited as one of the show’s titular traitors and tasked with lying to fellow competitors to reach the end undetected. Although she was eliminated in episode eight, her headbands, thoughtfully pursed lips and slippery tactics evoked ecstatic cries of “Mother!” from the internet.

But TV isn’t Shallow’s main job any more. Now, she works mostly as a life coach.

“Whatever your dreams may be, we’ll make them real together,” her website reads. “Whether it’s work, money, health, or purpose, I catalyze transformation.”

Who wouldn’t want her to tell them how to live?

Most of Shallow’s clients reach out to her because of Survivor, she tells me on a video call from her home in California. “They’ve seen what I’m capable of, so they’re like, well, if she’s telling me to do it …” she says.

Usually, Shallow’s “1:1 transformational coaching” costs between $1,500 and $25,000, depending on the length and frequency of your work together. But Shallow agrees to do a free, one-time coaching session with me for this story. She says her life coaching doesn’t get as much attention as her TV work.

“People know me as Parvati from Survivor, from the Traitors, but really my business that I do day-to-day is coaching,” she says.

I’m a Survivor fan. But as I prepare for our session, I’m not sure what I want from it. What exactly does a life coach do? What does a life coach who is also a reality star do? Unfortunately, I am not stranded on an island competing with big personalities for money, nor am I in a Scottish castle lying to Real Housewives while Alan Cumming parades around in capes.

I ask Shallow what her clients want help with, and she offers a few examples. One, a business owner, wants to improve their leadership skills. Another is unhappy in their marriage and figuring out next steps. One person has sleep issues and social anxiety. An accountant she works with “wants his life to be more fun”.

Fun sounds pretty good. Because my sense of self-worth is inextricably tied to my productivity – which seems fine and probably doesn’t need to be examined any further – I have a tendency to get bogged down in work and errands.

I also want more fun, I say.

I expect I will be asked to reflect on what I enjoy, or when I feel happiest. I’m worried I might be encouraged to get a hobby, or to dance more.

What transpires is far more involved. Shallow guides me through a meditation exercise. She asks about my relationship with my mother. She has me draw and name both my anxiety and my “higher self” (Kathy and Eleanor, respectively) and imagine a conversation between them.

What is happening?

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Shallow says her talent for connection is partly based on her nonjudgmental nature: “I will share all of my failures and mistakes if I think that will help the person I’m speaking with feel more safe with me.”

Part of it, she attributes to her upbringing. Shallow grew up in a yogic community led by a female guru who named her Parvati. There were regular chanting sessions, meditations and fire ceremonies. On the surface, she says, things were perfect. Adults in the community were always telling her how idyllic her childhood was. Below the surface, she claims, was “coercive control and abuses of power”.

The dynamics and power structures of the group were complicated and murky, she recalls. “As a child, I was able to feel the truth in my body, but not articulate it,” she says.

Her family left the community when she was nine, and didn’t speak much of it again. She says that the skills she developed there – negotiating intricate social dynamics and hearing what is left unsaid – helped her do well in the socially complicated atmosphere of Survivor.

Despite her success on the show, Shallow struggled. “Survivor was really quite traumatic for my body and mind,” she says.

When she returned home from her earlier seasons, she said, she had to readjust to the real world, where not everyone you meet is trying to throw you under the bus. Not only that, but her performance made her unpopular. Critics sneered at her flirtatiousness, and she earned the moniker the Black Widow for how effectively she and her all-female alliance took out the male competitors.

“I really didn’t like myself after I came back from [season 13],” she recalls. “And season 16, I won, but I was vilified. I was like: ‘No one will ever love me.’”

skip past newsletter promotionSign up to Well Actually

Practical advice, expert insights and answers to your questions about how to live a good life

after newsletter promotion

Survivor was really quite traumatic for my body and mindParvati Shallow

Floundering and unsure of what to do next, Shallow dove into what she calls a healing journey. She did yoga, meditation, breath work, hypnotherapy. She got married and worked for a consulting company, telling businesses how to grow and present themselves better.

Then she got pregnant, and wanted a job with more flexibility and control. At a speaking event, Shallow met Amber Krzys, a life coach in Los Angeles. Krzys invited Shallow to train with her.

Shallow liked that life coaching tapped into her curiosity about people.

“It’s not for people who are really in the pit. It’s for people who are doing well in their lives,” she says. “I was like, great. So I’m not going to be drained by people stuck in a loop.”

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

There are currently no legal, educational or licensing requirements for life coaches in the US or the UK. As such, the field can be something of a wild west in terms of providers’ qualifications and services.

Before she launched her coaching business in 2019, Shallow worked with Krzys as a client one-on-one for three months. She then enrolled in a six-month coaching program with Carolyn Freyer-Jones, a coach who developed the soul-centered professional coaching program at the University of Santa Monica, a center that specializes in “spiritual psychology”.

But Shallow believes her real qualifications have come from working. “I’m a big believer in on-the-job training,” she says. “Get me in the trenches, having conversations with people, learning through trial and error.”

Shallow doesn’t claim to know how or why coaching works. “I’m not a scientist,” she says. As she tells her clients: “If this works, if you feel better and your life is improving, that’s all the evidence you need.”

Right now, Shallow is working with five individual clients. Early in the pandemic she worked mostly with groups, but she’s dropped that for now because she’s also working on a book. She works with her clients for periods of three months, six months or a year, in sessions that last 60 or 90 minutes. New clients can only sign on for a three-month package at first, so Shallow can see if it’s a good fit.

“I’m not going to sign someone for a year who I haven’t worked with, because who knows if it’s going to be a good relationship,” she says. “I love my clients. I love them so much. I want them to have the biggest, fullest, most beautiful life. And that’s why I don’t work with everyone.”

During our session, Shallow is blisteringly attentive. She repeats my own words back to me so I can hear them. She tells me to write down the realizations I have. She mentions internal family systems, a psychotherapeutic approach that identifies sub-personalities within a person. She talks about the value of feelings, and how childhood experiences affect our romantic relationships. She compliments me, telling me I’m brave and vulnerable, and that “powerful wisdom” has allowed me to visualize the figure of Kathy, whom I have drawn on a notepad – a troubling character who looks like a mix of Edvard Munch’s The Scream and, well, Cathy. “You’ve got a gift,” she says.

I have been in therapy on and off for more than a decade, and most of this is not new to me. But I feel an intoxicating sense of validation. By the end of our call, I wish we were on Survivor so I could tell Shallow everything I know.

According to Shallow, a lot of the value of her coaching work simply comes from creating a space in which people feel they are accepted and heard. “There’s so much freedom for these people to make mistakes and fail and experiment,” she says. “Really the whole thing is permission to play.”

At the end of our session, she leans back, a satisfied smile on her face. She doesn’t plan for what a call will be, she says.

“You bring the content and I just go with it,” she says.

Am I having more fun as a result of our call? Am I less anxious and more able to goof off and enjoy myself? Not really. But not even the most transcendently affirming, charismatic coach slash reality star can reasonably be expected to undo 32 years of self-flagellation in one hour.

But since my session with Shallow, I have thought a lot about Kathy. When I feel the tingle of anxiety, I picture Kathy, and I think: “Wow, that was a really ugly drawing.” Weirdly, it does help a little.

∎