The first time I met Henry Louis Gates Jr raised more questions than it answered. It was the year 2000, I was still a teenager, and he – already a distinguished Harvard professor – was hosting a launch for his new BBC and PBS series Wonders of the African World.

I remember the occasion as a series of firsts – my first TV launch party, first documentary series I’d seen on African civilisations, first encounter with a real-life Harvard professor. I remember wondering whether the circumstances were normal. The venue was the British Museum, an institution that harbours a practically unprecedented quantity of colonial plunder. Was it, I wondered, a deliberately ironic choice? Were all Harvard professors as friendly and personable as Gates, whom everyone calls “Skip”, and was charmingly informal and kind? And perhaps most pressingly, was it normal for Harvard professor TV presenters to dress as Gates so memorably had, in shorts, socks, and a ranger’s hat?

Gates, whom I am meeting again for the first time since that day 24 years ago, remembers it for entirely different reasons. “I got in a lot of trouble for that show,” he says, cheerfully. “I was the first black film-maker to talk about African involvement in the slave trade.” And, he adds, with undeniable pride: “It was the first internet controversy involving black folks!”

The documentary, which followed Gates as he examined ancient civilisations from Axum to Nubia and Great Zimbabwe to Timbuktu, was indeed controversial. Alongside the African cultures he visited, he demonstrated great interest in African complicity in the transatlantic slave trade, an interest that managed to alienate almost everyone who was black.

African scholars complained that Gates revealed an approach to African culture through a western-centric, American lens. African-American scholars claimed his emphasis on black involvement “got the white man off the hook for the Atlantic slave trade”.

Gates, who is unfazed, amused even, by this kind of critique, doubled down, and has continued to do so ever since. “Erasing the role of black agents in the slave trade. That’s just dishonest. It’s bad history,” he says. “But the structures of racism, how they have been imposed on all black people for hundreds and hundreds of years, the modes of American slavery, the rollback after Reconstruction, the rise of white supremacy, the imposition of Jim Crow segregation. That’s what we need to focus on.”

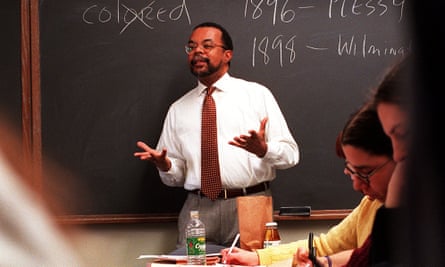

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

I’m speaking to Gates over Zoom. I’m in uncharacteristically rainy Los Angeles, he’s in sunny Miami. As we speak, he turns his laptop screen around, attempting to goad me – successfully – into jealousy at the sight of blue sky and serene ocean from his seaside condo. He is in Florida for a family wedding, and our call is periodically interrupted by good-natured family members coming in and out, as people mill around preparing for the big day. Family is important to Gates. His new book, The Black Box: Writing the Race, opens with the story of his grandchild Ellie, who inspired the book’s title.

Born recently to Gates’s daughter, who is mixed race, and his son-in-law, who is white, Ellie “will test about 87.5% European when she spits in the test tube,” Gates writes, adding that she “looks like an adorable little white girl”. And yet when Ellie was born, Gates’s priority, he reveals, was to make sure her parents registered her as a black child, ticking the “black” box on the form stating her race at birth. “And because of that arbitrary practice, a brilliant, beautiful little white-presenting female will be destined, throughout her life, to face the challenge of ‘proving’ that she is ‘black’,” Gates writes.

Any discomfort flowing from this – both Gates’s decision and his perception of it – is deliberately intended as a commentary on the discomfort of race itself. How can race not be contradictory, Gates suggests, when it was constructed in service of racism, and yet has been alchemised into a cultural identity celebrated by those most oppressed by it?

Imagine my surprise when I received my first DNA results, and I’m 49% white!

The Black Box applies this analysis to the lives of famous African Americans. The poet Phillis Wheatly, an enslaved young woman who was required to “prove” to white observers that she was capable of writing the poetry she so eloquently composed. The abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who constructed parental relationships – the reality being that he knew little of either his mother or father – to refute ideas, prevalent at the time, that if a black person was intellectual, that was because of white parentage. The history of what black Americans have both been called and called themselves, encompassing a fascinating and ongoing debate about the usage of “negro”, “coloured”, “African American”, and “black”.

A scholarly passion for this contrariness has become something of a trademark for Gates. “When the humanity of African Americans was questioned, they fought back by producing art and literature that their lives depended on,” he tells me. “They accepted the premise that there was a place in what [WEB Dubois] called the ‘kingdom of culture’ for them as well. Resurrecting that tradition, explicating it, that is my life’s work.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

That work began far away from Harvard, in a working-class black family in the hills of West Virginia. Gates’s father had two jobs, one at a paper mill and another as a janitor, and his mother was a home-keeper, and later a cleaner for a white family. After attending the local public school, Gates obtained an undergraduate place at Yale in 1969.

Although proudly black, the family vaguely knew it had white ancestry, particularly through Gates’s paternal grandfather. “My grandfather looked so white, we called him Casper, after Casper the Friendly Ghost,” Gates laughs. “I mean his skin was translucent!” Gates had thought one ancestor – his paternal great, great-grandfather – had been white. But when he tested his DNA, he discovered a different picture.

“Imagine my surprise when I received my first DNA results, and I’m 49% white!” he exclaims. “What that means is that half of my ancestors on my family tree for the last 500 years were white, and the other half were black, and that was an amazing lesson to me. So, what does that mean about identity? It means that I was socially constructed as a negro American when I was born in 1950. But my heritage, genetically, is enormously complicated.”

This discovery set Gates on a path that has become perhaps the dominant part of his legacy, as the host of a popular PBS show Finding Your Roots, in which he leads other prominent Americans of all racial backgrounds – figures including Oprah, Julia Roberts, Kerry Washington and Quincy Jones – on a similar journey, through DNA testing and genealogy, in which they trace their family tree.

“I have never tested an African American who didn’t have white ancestry,” Gates says. “And that’s quite remarkable to me.”

“Paradoxically these DNA tests deconstruct the racial essentialism we’ve inherited from the Enlightenment, because they show that we are all mixed,” he continues. “It’s a mode of calling those categories into question, showing scientifically that they were fictions, and freeing us from the discourse that sought to imprison us in the black box, the white box, the Native American box.”

The tightrope Gates walks lies in rejecting blackness as a racial category, while embracing it as a cultural tradition. His most recent PBS documentary series, Gospel, which relays the origin story of gospel music, is perhaps my favourite work of his, celebrating both the heartbreaking beauty of black spiritual tradition in America, and its seismic impact on global culture.

When I share my emotion at the series, Gates is unable to resist subverting the theme. He bursts into a rendition of Can the Circle Be Unbroken?, a 1930s country number by the white gospel group the Carter Family.

“[On a cold and] cloudy day/ when I saw the hearse come rollin’/ for to carry my mother away/ Will that circle be unbroken/ By and by, Lord, by and by,” he sings, in a surprisingly rich tenor. “White people wrote that song, black people love that song!” he exclaims.

I just could not imagine Americans deciding to pay for all that our ancestors suffered

The current climate, in which political tribes are more polarised than ever, has only deepened his resolve to push back against the idea that black people should all agree. In this, he sometimes comes across as a man from another age – a more charming one, real or imagined – in which everyone could sit down together and work it all out.

“I grew up in a working-class town. People are goodhearted. They want what everybody else wants: to make enough money to live comfortably, to send their kids to college, to be able to go on vacation, to have leisure time, to have some joy in their life and not just be punished by drudgery, not have economic anxiety,” he says.

Gates’s stance on reparations is a case in point. The murder of George Floyd in 2020, and the current threat to black history studies from rightwing Republicans – some of Gates’s own work has been banned from schools in Florida under Governor Ron DeSantis – have only accelerated calls for restorative justice for enslavement.

Gates acknowledges the wrongs but disagrees with the solution. “Affirmative action plans go a long way… I think that’s a form of reparation,” he says. “But I just could not imagine any group of Americans deciding to dip into their pockets and pay a cash settlement for all that our enslaved ancestors suffered. I don’t think that’s realistic.”

When I disagree – citing examples of other societies that have paid reparations, Gates is firm. He even describes calls for reparations as “racial bullying”. “The bottom line is, you can’t bully people with calls for reparations because of the legacy of slavery,” he insists. “So we need leaders who are thoughtful and nuanced and sensitive. I should know. I’ve been in America for 73 years.”

Gates’s optimistic view of American decency was famously pushed to breaking point in 2009, when he – already a famous professor and TV personality – achieved unwelcome notoriety. Returning home from filming in China, he was struggling with the lock on his door, as he entered his own property. A call from a neighbour – who reported a suspicious black male attempting to enter a house – led to the arrival of police. Gates was initially suspected of breaking into his own home. When it was established that he lived at the property, he was arrested anyway for disorderly conduct. Widespread coverage – which made international news – pictured an angry Gates, handcuffed, being led away from his own front porch.

The events are still painful for Gates, who describes them as “a nightmare”. “You know, being arrested is no joke,” he recalls. “I was fingerprinted. I was put in a jail cell. And I’m slightly claustrophobic, so being in a cell, that’s just horrendous. It was a bad day. And you know what? It made me a forever proponent of prison reform. Because as a poor person, a black person in the prison system – you don’t have a chance.”

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Gates was released after Harvard sent its lawyers over. Further controversy ensued when President Barack Obama commented on the debacle, calling the police’s decision to arrest Gates “stupid”. The entire affair was resolved in a meeting at the White House in which Gates sat down for a beer with the officer who arrested him, the president, and vice-president Joe Biden.

The “beer summit”, as it became known, sparked wider conversations about racial discrimination in policing. Gates took a conciliatory line. “My heart went out to the officer when he told me he was just scared,” Gates says. “He had just wanted to go home that night to his wife. We shook hands and he gave me the handcuffs he had used to arrest me. And they’re now in an exhibit in the Smithsonian,” he adds, with a weary air of triumphalism.

Beers with a well-intentioned black president and messages of racial conciliation seem a lifetime away in the current political climate. Yet Gates says his own teaching practice remains unthreatened by fears of censorship or backlash. “Fortunately, I have the freedom to teach, whatever way that I want and whatever content that I want,” he says.

Gates has been protected, perhaps, by his refusal to conform to the norms of either academic or celebrity life. He is one of the few people to have achieved fame as an academic, thanks to his long TV career. He credits that not to American broadcasters, but to his time in Britain, early on in his career. “My time in the UK was fundamental,” he says.

That story began at Cambridge University, where Gates studied on a postgraduate fellowship, with plans to return to the US to study medicine. Then he encountered Nobel prize-winning writer Wole Soyinka. “I read African literature and mythology with Soyinka, which I took to like a fish to water,” Gates beams. And another black great, the now famous philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, was Gates’s contemporary and one of his few fellow black students at Clare College. Appiah and Soyinka became his close friends.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

“One time we went to this Indian restaurant in Cambridge,” Gates recounts. “And Soyinka brings his own chilli. I mean, this Nigerian chilli he would make and carry with him – it was engine oil! And they said to me: we are from your future. We brought you here to tell you you’re not going to be a doctor. You are meant to be a professor. You’re going to be a scholar of African and African-American studies, and you’re going to make a difference.”

The prophetic nature of those remarks must have become obvious when Gates’s first book, The Signifying Monkey, was published in 1988, applying post-structuralist analysis to African-American vernacular and literary traditions. Since then, Gates has made a name for himself as a leading voice of African-American literary and cultural history. Yet it is his TV career that put him on a steady path to becoming an American national treasure. It was the British producer Jane Root, Gates tells me, who recruited him to present an episode of the long-running BBC series Great Railway Journeys in 1996, travelling with his two daughters through southern Africa.

“The whole conceit was this professor of African-American studies taking his mixed-race daughters to Africa to find their roots, only for them to say: ‘Our roots are in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I’ve got nothing left in Africa, I want a Big Mac,’” Gates laughs. “The Guardian called it National Lampoon Goes to Africa, and that was just so honest and fresh. I would be giving my daughters this pompous lectures about Livingstone and, you know, they’d be rolling their eyes. And it was great.”

The success of that episode led to Gates hosting an entire series, Wonders of the African World, the show where I first met him all those years ago. “My whole life as a film-maker, I owe it to Jane Root, and to the BBC,” he says.

The concept so central to Wonders, of the descendants of the enslaved reconnecting with Africa, is as old as the enslavement that displaced them. Yet its modern iteration has exploded in recent years. Ghana, the west African nation that has long positioned itself as a hub for the “return”, now regularly records hundreds of thousands of additional visitors from the black diaspora, with festivals celebrating global blackness and ancestral connection. “I love it!” Gates says, of this growing phenomenon. “I think all African Americans should do two things. Take a DNA test to see where in Africa they’re from. And I think they should visit the continent.”

The return is a joyful movement in which black people seek to heal the bonds severed by enslavement and globalisation. Yet if underneath it lies a pessimism – that racism makes western nations unliveable – it is not one that Gates shares.

He acknowledges that America is broken. “I remember under John Kennedy and certainly with Bobby Kennedy, and with Martin Luther King, we thought poverty was a disease that could be cured. No one thinks that today,” he laments. But rather than offering a way out, he believes in the country’s redemption, and hopes he and his work will play a role. “We have to fix it,” he says. “And we have to fix it together.”

In typical contrary fashion, Gates turns to histories rooted in the darkest side of America’s racial capitalism to find inspiration for believing in America’s potential. At the turn of the 20th century, when black women faced racist characterisation as “thieves and prostitutes”, they retaliated by forming “coloured women’s clubs”, to improve their image, foster racial pride, and advocate civil rights.

“I think of that movement,” Gates says. “Their motto was ‘lifting as we climb’. And I think that should be the motto of American capitalism. We lift, as we climb.”

The Black Box: Writing the Race by Henry Louis Gates Jr is published by Penguin (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply