Most of us have an indecent curiosity about what other people do in private. Sex and tax, for instance: “What do you do in bed?” and “How much do you earn?” are the questions that lurk under almost all profile journalism and biography. There’s a particular species of prurience that concerns the working habits of actors: what do you do in rehearsals?

I’m not immune to this prurience. Even when I was running the National Theatre I rarely witnessed more than fleeting fragments of other directors’ rehearsals. No one likes to be observed; rehearsals are a private province. I once asked Paul Scofield if he’d mind if a visiting Japanese director could sit in rehearsals. “Thank you for asking,” he said, “but I’m afraid the answer is no. Peter Hall once brought Placido Domingo into rehearsals of Othello without asking me. I never forgave him.”

At the beginning of rehearsals the actors view the landscape with the innocent optimism of new settlers, sharing a common aim and bound by the same social rules. They’re stridently individualistic and yet have to bury their egos for the good of the whole. They have to work to a common pulse, even if each chooses a different tempo. They’re of uneven abilities and yet they have to subscribe to a democracy of talent, underwritten by a generosity of spirit. It’s a model society that has been formed for pleasure – for play – which is why I’ve often heard actors say, as Cillian Murphy did recently on Desert Island Discs, that they enjoy theatre rehearsals more than performance.

The first day of rehearsals is always the same: nervousness shrouds everyone in a dense fog. Some directors do exercises to dispel the mutual unfamiliarity. “Fucking games,” Michael Gambon used to call them, but then he also said: “The theatre should be a dirty, radical place. Screaming at night from the stage about the plight of mankind and the world is ridiculous if you can’t smoke.”

I like actors to talk about the world of the play and the way it touches on their lives. I’ve acquired a continent of knowledge from actors, shared their secrets – and mine – about family, love, violence, fear. There’s an unspoken guarantee of discretion in the rehearsal room. When I was rehearsing for a revival of my production of Guys and Dolls, we reached Sky Masterson’s line: “Obadiah, that’s my real name,” and Sky’s understudy, an actor from Belfast, said: “When I was 12, I was given a new name. We’d had some trouble with the IRA and when I went off to school my mammy said: ‘You’ve got a new name, it’s Ken McElroy.’ So I wrote it on my palm, scared shitless I’d forget.”

Rehearsals are a world like any other, but in no other world have I laughed so much or cried so openly

Sitting round a table, letting actors talk without censure has its perils. Rehearsing The Crucible on Broadway with Arthur Miller, I encouraged all the cast to talk freely about the play and take advantage of the author’s presence. The youngest member of the cast – a 12-year-old girl – had of course never encountered the play, let alone the name of the author. She talked – and how she talked – about what she thought about the play and how it should be acted until Liam Neeson said: “Do you not think, Macy, it might be time for Arthur to get a word in?”

Rehearsals are a time when actors should experiment, they should invent, explore, discuss, dispute and make fools of themselves. It’s the director’s job to ensure a secure environment where there’s no sense of fear, foolishness, blame, shame, or failure. And if this sounds like an ideal family, it should be remembered that it’s the director’s particular privilege to choose who becomes a member of that family.

Some gifted actors seem exasperatingly slow in rehearsals, some bewilderingly stubborn, some alarmingly quick, leaping from conclusion to conclusion like scaffolders on rooftops. Sometimes a star will soak up the energy of the actors who surround them, sucking the oxygen out of the room. And sometimes a director will do this. Actors, or more often journalists, are curious about “method” (or the Method), but unless they’re subject to the collective dictatorship of an expressionistic production, or of a musical, most actors will pick up ideas, images, comic business, like scavenging mudlarks.

There comes a time when this little utopia becomes corrupted by reality and anxiety steals into the room: lines have to be learned and choices have to be made. Then, sometimes alarmingly late in rehearsals, the buoyant travellers encounter an obstacle: the first run-through. A smell of danger enters the room, as well as a guarded excitement in seeing the play as a whole and their fellow actors revealing themselves. When we first ran King Lear with Ian Holm, it was huge and as inchoate as the sea. “Let’s do it again,” he said.

Run-throughs are always a shadow of what will end up on stage in performance, but the first one, stuttering and clumsy, always seems like a mammoth stumbling through a frozen mist, engendering part awe, part hope, part terror. But after a few days rehearsal, the sun comes out, the mist evaporates and the production comes assertively alive, shapely and eloquent. Or not. Then we look to one another for reassurance. “It’ll get better,” Judi Dench said to me after a depressing run-though of Amy’s View. And it did. I’ve said the same thing to actors, once to Dandy Nichols. “It won’t,” she said. And she was right.

Rehearsals are a world like any other, but in no other world have I laughed so much or cried so openly. Working on a farce with Tony Sher, I had to lie down on the floor to control myself; and I often felt tears on my cheeks watching Eileen Atkins in The Night of the Iguana or Lia Williams in Skylight. What fun, what larks, what luck, what joy, to be able to spend your days in the company of people who you like and admire and whose talent and wit and imagination are so life-enhancing. “It beats working,” John Thaw used to say.

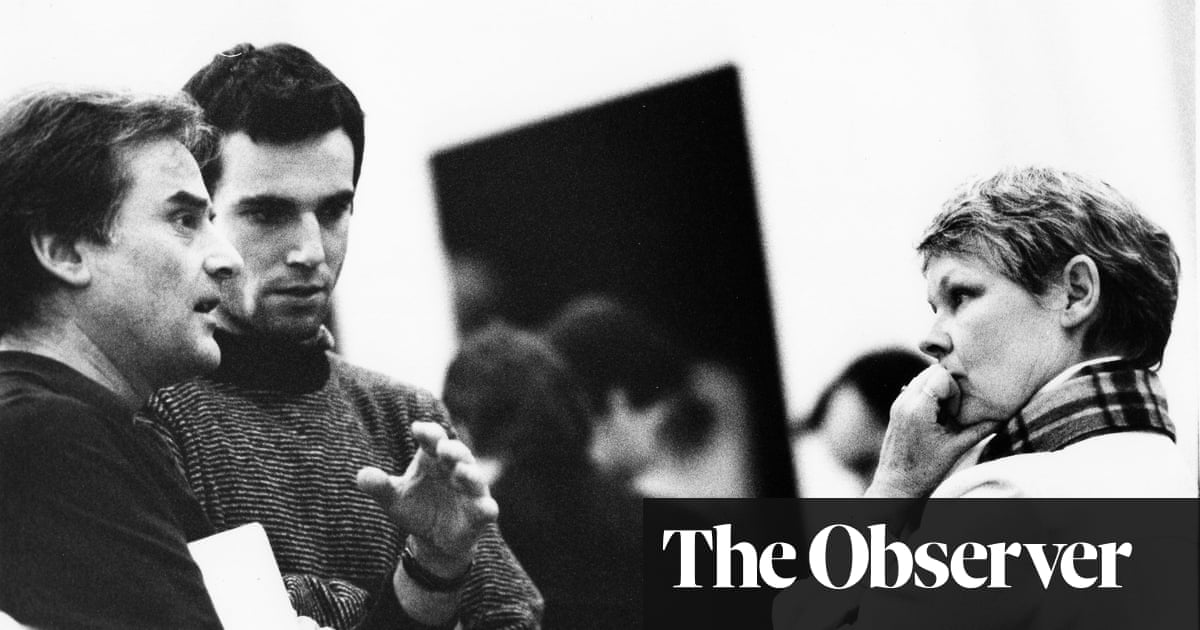

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Lindsay Duncan: ‘Instead of stressing and fannying around, just look at the text and say the words’

Over a long and distinguished stage career, Duncan has worked with the likes of Harold Pinter and Caryl Churchill and won two Olivier awards and a Tony. She currently stars as Dora in Dear Octopus at the National theatre, until 27 March

The first thing that crops up when I think about rehearsals is that I don’t like games. I really don’t. I understand why people enjoy them, but I find them slightly patronising. It’s like, Ooh, look at these people, how will they know how to interact and learn how to trust one another? And I go, well, for fuck’s sake, we’re actors, this is what we do. Games also waste very precious time. I don’t think I’ve ever been in a situation where there’s too much time to rehearse. There’s never enough. So I find things that eat it up quite irritating.

There is nothing like going to the play and getting your hands on it, your mouth on it, your body, your brain, everything

The last time I played games in rehearsal, we were asked to choose an animal to be. I was so angry, I started frantically waving my hands in front of me. I said: “I’m a dog digging a hole into which I can climb.” I just thought, this is not helping, we have a complicated play to do and what could be more stimulating and exciting than mining a really good piece of writing? It’s endlessly challenging and thrilling. You don’t need to throw a ball at one another. You’re doing that all the time with words and ideas.

When I did Caryl Churchill’s Top Girls, Max Stafford-Clark was directing it and he worked in terms of actioning. Your character has to find a verb to describe what they’re doing with a sentence or in the scene, and that’s discussed with the group so everybody knows what someone else is trying to achieve. It becomes very specific. Of course, you can depart from that at a later point, because things shift as you learn more, but it’s a useful tool if you get lost.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

In 2000, I worked with Harold Pinter on a double bill he directed at the Almeida of his first and last plays, The Room and Celebration. He was very hands-off as a director. His work is absolutely finished, every word is chosen and just delivers, like bullets from a gun. He left us alone to a great extent. For Celebration, I was deputed by other members of the cast to ask exactly how common our characters were supposed to be. Everyone was frightened of Harold, but I’d worked with him a few times and I really loved that man. When I asked him, he said: “I would refer you to the text.” And of course, he was absolutely right. Instead of stressing and fannying around, just look at the text and say the words, and there you’ll be.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Dear Octopus had a very happy rehearsal period. [Director] Emily Burns is very sharp about text and she brings the most marvellous energy to a room. You want a rehearsal room to be warm and inviting and happy, but you also want it to have a little bit of challenge – we’re not there to hang out, we’re there to achieve something, to unlock the play. So she didn’t waste a lot of time and got straight into it. There is nothing like going to the play and getting your hands on it, your mouth on it, your body, your brain, everything.

It can be an anxious time because everything in you is questing, and all the time you’re getting these messages that it isn’t there yet. So I will fret. But if I’m playing an intense role, I don’t find it hard to shake it off when I leave the building. What I carry home with me is more the concerns about the work. If you’ve found something that is dark or upsetting, it’s a discovery and you’re very pleased about that. The main question for me is, is it honest? If it is, I can leave it at work, because I’ve done my job. I’m not a method actor. I have no intention of living it out. If I did, I’d probably be in an asylum by now.

There’s a sense in which the rehearsal process continues after the run has started, because theatre is a live art form, and the minute you start to feel comfortable, you’re risking something deadly. You really do have to find things truthfully every night. It is wearing, repeating a play, but on another level it’s exciting, because there’s always the possibility that you can do better. So, for me, I do like input throughout a run from the associate director or director. You need somebody to say: “You’re a little bit too pleased with yourself there,” or: “The timing has gone.” Because that’s what you’re aiming for: to make it absolutely alive, every single performance.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Adjoa Andoh: ‘Come performance time, you can be shooting ping-pong balls at my face and the words will still be coming out of my mouth’

Known for playing Lady Danbury in Bridgerton, Andoh has worked extensively in theatre, starring in His Dark Materials at the National and Julius Caesar at the RSC. She co-directed and starred in Richard II at the Globe in 2019 and directed and starred in Richard III last year at the Liverpool Playhouse

There’s no such thing as a typical rehearsal process, but there are aspects that recur – such as nerves. You’re always thinking: why am I here, I shouldn’t be doing this, this is going to be embarrassing. But I think it’s a good and humbling part of the process. The anxiety makes you focus. It’s also a lovely test run for the blinding nerves that you will have on press night.

Rehearsing is 100% an emotional process. You have to come open-hearted to it and really dig into yourself

The length of the rehearsal depends on the budget. At the National or the RSC, you may get eight or 10 weeks, whereas at a regional theatre you may get three and a half. So the playing field is topsy-turvy. Whether a longer period is a luxury or a strain depends on how complicated it is. For The Revenger’s Tragedy at the National in 2008, we had a good eight weeks, but we had opera in it, and revolving stages, and puppetry, and murder and prosthetic cocks. It was fabulous. We did yoga every morning before we started rehearsing. To begin with I was rolling my eyes to the ceiling, but by the end I just loved it.

For David Hare’s Stuff Happens at the National, directed by Nick Hytner, we had workshops where we were interviewing people such as Robin Cook, Christiane Amanpour and James Rubin about the Iraq war, which had started the year before. It was the most extraordinary process. You felt you were part of the national conversation, really hot on the disastrous fallout of that military incursion.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

By contrast, for Nights at the Circus directed by Emma Rice, we went to Cornwall, stayed in holiday lets and walked up and down hills. We rehearsed in a barn and people took it in turns to cook. That was a very different approach.

The French for rehearsals is répétitions, and that’s what it is for me when I’m learning lines: you just repeat them and repeat them. I find motion is very helpful. Before I lost my doggie, I would quite often learn lines walking around the park; now I pace the kitchen. I just need to know that come performance time, you can be shooting ping-pong balls directly at my face and the words will still be coming out of my mouth.

Rehearsing is 100% an emotional process. You have to come open-hearted to it and really dig into yourself. In New York the other day, I went to see Prayer for the French Republic. It is a very emotionally conflicted play and there’s a certain moment when somebody asks a question, and all 800 people in that space leaned forward and you could have heard a pin drop as we waited for the reply. And I thought, that’s what rehearsals are for – for this moment where the whole audience is of one mind, leaning in.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Danny Sapani: ‘You are immersing yourself in human pain. It affects your dreams, your physical life, how you relate to your family’

On screen, Sapani has appeared in Killing Eve and Black Panther; his stage roles include Jason in Medea at the National. As King Lear in Yaël Farber’s new production at the Almeida, running until 30 March, the Observer’s Susannah Clapp describes him as “commanding, the bass note from which everything springs”

For King Lear, the director Yaël Farber and I started to share ideas last October, months before we opened. It’s quite unusual for me, or any actor, to have that much time to prepare something, but it felt like the part needed it. We would meet on Zoom and discuss how to tell the story. It was also about making sure that, as the lead, I kept a happy ship, because it can be very easy to tip into dissent, particularly with Yaël, who has a very singular way of working. She likes actors to bring their bodies to the work and to be able to push themselves beyond what they’re used to doing – and that takes a lot of trust.

In most productions, you begin by meeting the extended family of the theatre over croissants and coffee. Then you might have a design chat to get a sense of the set and the costume design, and then sit down around a table and read the play as a company, breaking it down so we’re all understanding what the story is. That might take a few days. Eventually, once everybody’s got the words in their heads, you start to put some of what you’ve discussed on its feet, trying some blocking, some props, some movement.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

The difference with Yaël’s approach is that we would be improvising physical interpretations before we got hung up on the words. There was one fantastic exercise we did where the company was creating the king. I was in the middle and the other actors moved around me in a way that showed reverence and respect, and then slowly that reverence started to turn into something else, where they were taking from my body. It’s the dichotomy of being a head of state, where you receive but are also taken from – there’s a cost. I’ve discovered more and more as we’ve come to the stage how lonely Lear is, and it’s only through really immersing yourself in the character during rehearsal that you get these insights that are often beyond the brain. You have to let it live in the body and understand what that feels like before you can really portray it.

It’s interesting how we deal with really tough stories. I remember doing a play at the National called The Overwhelming, about the Rwandan genocide. We did a lot of research, speaking to journalists and reading books, and it was a lot to carry. In these situations, you find a way as a company to cope, and often it’s by finding a sort of humour and a way to look after one another, because it does take its toll, you are immersing yourself in human pain. It affects your dreams, your physical life, how you relate to your family. So the ways of coping can be quite dark but also extraordinary in their closeness and care. It’s a very short period of your life, but you build connections with people that you don’t fully understand, and you can meet them years later and still have it. It’s a bond that’s never broken.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Jade Anouka: ‘I’ve had instances in the rehearsal room where I haven’t felt completely looked after or safe’

Anouka began her career at the RSC, appearing in The Penelopiad in 2007. She starred in Phyllida Lloyd’s all-female Shakespeare trilogy (2012-17), “one of the most important theatrical events of the past 20 years,” according to the Observer. On TV she played Ruta Skadi in His Dark Materials and will appear in the series Dune: Prophecy later this year

When I did Julius Caesar with Phyllida Lloyd [in 2012], that rehearsal process was mad. We just tried so much stuff out and there was a lot that ended up on the cutting-room floor. Sometimes at rehearsals the director tells you exactly what will happen: start here, end there. This was like: “Whoa, let’s just get a load of, I don’t know, wetsuits and, OK, so we’re all in wetsuits, now let’s try this and try that.” It was kind of mad. But Phyllida is a great director and she said she would never ask us to do anything that she wouldn’t do herself. And she stuck to her guns. If she asked us to do anything crazy, she would do it first to prove that she believed in the idea enough. Once she got into a big plastic bag and got somebody to drag her across the room covered in blood.

That experience was amazing but I’ve definitely had instances in the rehearsal room where I haven’t felt completely looked after or safe. A director might ask you to do something and you don’t understand why. It might be a fight scene and you feel, we shouldn’t be improvising this, or it might be more on an emotional level. There’s a power dynamic in a rehearsal, especially when you’re new and you feel like you can’t say no. Younger actors are always so grateful to get the job and don’t want anything to mess up. If a director wants a performer to go there, they need to make sure that they’re looked after, protected.

You have the best laughs in rehearsals and you go through the whole plethora of emotions, but there’s always a time around three weeks in where you’re like: “I’ve only got a week before tech and I don’t know what I’m doing.” I always have a freak-out at that point. But then you get the final week, and suddenly, somehow, it all randomly fits together. You’re like: “Wait a minute, we know this. We’re ready.”

As much as I love rehearsals, there’s nothing that can beat performing. I used to do middle-distance running and there’s a moment where you click off and you don’t feel your body or the tiredness, you’re just flowing. And you get moments like that on stage. It doesn’t always happen, but when it does, I’m like, this is what it’s all about. This trumps everything else.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

Mark Gatiss: ‘It’s reassuring that church halls are still the norm for rehearsals. You feel that you’re part of an ancient tradition’

A member of the League of Gentlemen, which started out as a stage act before transferring to TV, Gatiss went on to create BBC’s Sherlock with Steven Moffat. He plays John Gielgud in The Motive and the Cue at the Noël Coward theatre until 23 March

Too much time spent on rehearsals can be deadly. Unless they’re absolutely epic, most plays don’t need weeks and weeks of table work, which everyone dreads. Obviously you want to talk about it, but the faster you can get the play on its feet – to actually start doing the lines rather than debating the meaning – the better, because then you can make discoveries as you go along.

There was one rehearsal where we’d been around the table for far too long and I remember watching as, one by one, everybody around the table nodded off, because it was just so tedious. You find yourself droning on, and then you start to wonder: am I just talking for the sake of it? I don’t actually have an opinion on this.

Sometimes I glance across the table at someone else’s script and it’s colour-coded and covered in thousands of intense thoughts, and I look down at my script and there’s just a cock and balls drawing. I’m afraid that’s my process.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

But there have been some amazing and electrifying rehearsals. I did 55 Days with Howard Davies, a wonderful director, and we got up on our feet straight away and talked about it as we went along. I found that really exciting. He brought all kinds of interesting things to it and widened the discussion without losing sight of the play itself.

One thing that’s burned into my brain is rehearsing The Recruiting Officer with Josie Rourke. We had a brilliant time, but I’m pretty dyspraxic and I had to do a sword fight with Tobias Menzies. And I hated that. It was like PE. Tobias is a natural athlete and a natural fencer, but I found it so difficult. It really got to me. I found one of the gloves the other day in a cupboard and it’s still got a blood stain on it from overpractice.

For The Motive and the Cue, which is about the rehearsals for John Gielgud’s production of Hamlet, we had quite a long time to rehearse, but it’s a big play and it didn’t feel like we were treading water. There were levels of meta-ness that at times were extraordinary. We were in a rehearsal room that was set up to look like a rehearsal room. There were people around the edges of the rehearsal who were in the scene, and then people around the edges of that who were not. There was real stage management and pretend stage management. Real director, fake director. The blurring of fact and fiction was very strange. For a lot of actor friends who’ve seen it, they find some of the scenes when things go badly wrong between Gielgud and Richard Burton very uncomfortable because they feel like they’ve been there – we’ve all been there at some point.

The National is wonderfully equipped for rehearsals, but it’s reassuring that church halls are still the norm. It makes you feel like you’re part of an ancient tradition. I’ve been in most of them over the years – the American church on Tottenham Court Road is very popular. There’s something lovely about the slightly damp, Sunday quality to those places. And I enjoy turning up and watching people troop in, and it’s like, oh, here we go. And maybe you know some of them, maybe you don’t know any of them. And then, somehow or other, four or five weeks later, you have a thing.

Sometimes there’s just days or hours to go and you wonder how this could possibly come together into something coherent. I remember vividly when we did our last League of Gentleman tour, the first show was in Barnstaple. The clock was just ticking down, we were still teching all kinds of things, and I said something like: “Let’s do that once the show has started,” and Reece Shearsmith bellowed: “What show?!” Because it seemed impossible to imagine we were going to do it in about 45 minutes, but we were, it was just ridiculous. I always laughed about that. “What show?!”

∎