It opens with a back-lit wine cellar, then the camera pans back; past the double garage and the fifth bedroom. Past the home theatre and the powder room. With a chill out soundtrack and a colour palette of overwhelming whiteness, the YouTube video promoting the Artisan 55 display home takes us into a double-height ceiling above the dining room. We swerve left to the kitchen and its butler’s pantry, and swing right to the family room and an expansive L-shaped lounge. Upstairs, of course, there are four more bedrooms – each with their own walk-in wardrobes and an en suite bathroom – and another living area simply designated “leisure”.

At more than 400 square metres, the Artisan is substantially larger than the average new Australian home but it is emblematic of how over the past few decades, Australia has become home, by some measures, to the largest average new houses on the planet.

I watch the Artisan video from the dining table of my own home, an 1880s row house measuring perhaps 110 or 120 sq metres – a size more typical of new houses in Europe, or Japan. By 2024 Australian standards, the house is claustrophobic. It has three moderate bedrooms, a single living room, solitary bathroom and a dining space off the kitchen. It is so small by contemporary Australian suburban measure that all new visitors to it are met with a laugh and self-deprecating reference to the “grand tour”.

Sign up for a weekly email featuring our best reads

Our reference points of small and big, of enough and not enough, have shifted dramatically over the last century. In 1960, our average new homes measured about 100 sq metres. By 1984, it reached about 162 sq metres. Now, it’s more than 230 sq metres. In the 1930s this home of mine, which today feels barely able to contain a family of four, housed the White family – a household of 11.

What has happened to Australian houses in that time? How did we get here, to the land of some of the largest average homes on Earth? And can we ever turn back the tide on big house culture?

‘I want one of those’

How we got here begins, in a way, on a leafy avenue in Burwood, a suburb on the boundaries of Sydney’s inner west.

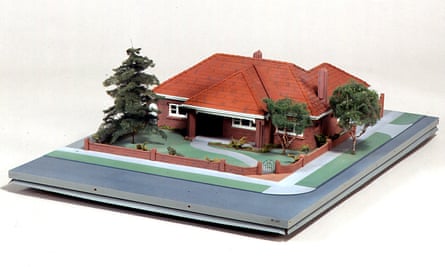

Along the short, but wide and handsome Appian Way – bisected by a grass tennis court – are stately Federation homes, set back from the footpath by lush front gardens. They are stationed apart from one another – verandas and gardens and paths establish clear boundaries, turrets and gables showcase wealth and taste – each a miniature castle built for a new world.

![‘Appian Way [pictured in 1970] became the place every homeowner went to and said “I want one of those”,’ says architect Tone Wheeler.](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/3c01d495620f4cbd5a4a54a89c73b227ee42bc64/125_131_1380_828/master/1380.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none) View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

“1896/1897,” says architect Tone Wheeler without hesitation. This is one of three key dates the president of the Australian Architecture Association says marks Australia’s progress to big house culture. As federation neared, local councils were determined to dispense with the smaller terrace homes and workers cottages of the past, the slums which had proven unsightly and problematic in the larger cities. So they called for larger subdivisions of land, he says. “That’s where the quarter-acre [1,000-sq-metre] block comes from.”

“Appian Way became the place every homeowner went to and said ‘I want one of those’,” says Wheeler. No longer was the colony a land of crowded dirty cities and a vast pastoral land beyond, scattered with a few grand homes tended to by house staff. Appian Way, and the quarter-acre blocks divvied up across the country, became a new form of national aspiration and identity. “Suddenly it became suburbia, detached houses, individual style.”

It goes from being your domestic life, your home where you raise a family, to being property and productTone Wheeler

It set the standard for the Australian dream in a country that was in the business of defining its place and aspirations. The big house. The quarter-acre block. A place apart from others. It was, in truth, a dream only available to the upper middle classes, but the rest of us have been chasing it ever since.

Wheeler next identifies 1932, when auctioneer AV Jennings bought a plot of land in Melbourne for the purpose of building new homes (having run out of existing homes to sell himself) as a second turning point. It would ultimately prove to be the beginning of a project home behemoth – though the global economy and events would intervene to prevent that model from kicking off just yet.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

During the height of the second world war, when battalions of the renting class were out fighting and dying in foreign lands, the dream of “one little piece of earth with a house and garden which is ours; to which we can withdraw … into which no stranger may come against our will” was extolled by the prime minister of the time, Robert Menzies. The desire to own a house of one’s own was, he declared, a “noble instinct”.

After the war, new homes for the ordinary person to own were finally built at mass, home ownership boomed but labour and material shortages kept a natural cap on house sizes. That enforced modesty, however, would not last.

The aspirations set by the Appian Way era, the model set by AV Jennings in the 1930s, and the sense of righteous entitlement to home ownership set by Menzies collide in the 1970s. This is the decade – around 1975/76 – says Wheeler, when project homes shifted from single-storey builds, to two storeys.

“The two-storey house is the thing that destroyed the bungalow idea of single-storey Sydney and Melbourne,” says Wheeler. “When you have two-storey houses it enables you to have a much bigger house, to separate things out, to put children’s rooms separate from parents rooms. And then what do you fill these rooms with? You have a parents’ retreat, a rumpus room, now you have a cinema room, a games room, the kitchen gets bigger, you get a butler’s pantry.

“It goes from being your domestic life, your home where you raise a family, to being property and product.”

And with a product, bigger is better.

The monetisation of homes

Our homes have always been a display of our individual wealth. But over the past three decades in Australia, homes have gone from being a display of wealth to a vehicle for creating it.

“We are now thinking of housing as our major investment in our life,” says Hannah Lewi, professor of architecture at the University of Melbourne and co-director of the Australian Centre for Architectural History and Urban and Cultural Heritage. “Once it gets embroiled completely with the major financial equation in someone’s life, then maximising becomes the main objective.”

As a home has become something more than shelter and into a speculative investment, says Wheeler, the way we think about that space becomes “skewed”. “People think,” he says, “‘We could do with a house that’s 150 sq metres, but when time comes to sell we want to be much bigger, so we’ll build a 250 sq metre, so it’ll be worth more money – even if we don’t need it.’” (In 2019-2020, the ABS found that 77% of households in Australia had at least one bedroom spare).

“Almost everyone we’ve ever met [as architects] is interested in the value of their property going up.”

The fact that any gain in value on the home you reside in is not subject to tax and is not included in means testing for the age pension, says Hal Pawson, professor of housing research and policy and associate director at UNSW’s City Futures Research Centre, means it makes financial sense for those who own homes to build bigger and bigger to get the greatest tax-free benefit.

Often, debate about McMansions is tinged with condescension; the bourgeois inner city wringing its hands at the unsophisticated aspirations of those in the new outer suburbs. However, the expansion of existing homes in these established areas is an important part of the explosion of our national house footprint over the past 20 to 30 years, says Pawson. Modest bungalows knocked down and replaced with hulking two-storey homes, semis gutted and rebuilt to double in size. Inner suburban streetscapes forever dotted with council approval signs cable-tied to front gates, alerting neighbours to renovations afoot.

“It isn’t just the outer suburbs,” says Pawson.

skip past newsletter promotionSign up to Five Great Reads

Each week our editors select five of the most interesting, entertaining and thoughtful reads published by Guardian Australia and our international colleagues. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Saturday morning

after newsletter promotion

“The cultural preference [for larger homes] is a pretty widely shared one.”

‘Everyone has to have their own space’

Aside from the evolution of homes from places of domestic life to vehicles for financial gain, something else has happened to the way we think about space in our homes.

As I sit in my home and imagine, as I sometimes do, where the nine White children may have fit, it becomes quite clear that they did not. That much of their lives must have been spent in public places – along the street, in the local park, perhaps down at the municipal pool – and that time spent within the home would have involved little privacy and limited individual possessions.

“There seems to be a shift in the way social dynamics work in families,” says Lewi. “Everyone has to have their own space. They must have privacy. And that seems to have to happen at an earlier age.”

Alongside the shift within family dynamics, some have likened modern suburbia to places of miniature fortresses, where unscheduled interaction with others – neighbours and strangers alike – is limited by the retreat into our ever-larger homes.

“All the things that were the glue of the suburbs – pools, bowling clubs, civic centres, cinemas, baby centres – gradually a lot of that public realm interaction has fallen away,” says Lewi. “More and more things are atomised into people’s homes. Homes have to do multi-functional things.”

Wheeler says the desire to have more of one’s own private space increases as one’s wealth does, but “Australians have put that on steroids.”

The idea of what children, families or any household needs is always informed by what we see around us. Which is why what is acceptable in one era is unthinkable a few decades later, and why in Finland people seem no less happy with their houses less than half the size of Australian ones. A 2019 American study found that people’s satisfaction with their homes does generally rise with more space, but only until the houses in their neighbourhood get bigger.

When the NSW government this year announced plans to increase density in Sydney, the premier, Chris Minns, remarked that the city was the 20th most expensive in the world, but the 800th most dense. Indeed, Australian cities are notoriously some of the world’s most expensive but not, says Pawson, when we compare how much we get for the money. A 2023 study by the Urban Land Institute found that, when considering cost per square metre of new and existing homes, Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane homes were cheaper than those in Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Hangzhou, Tokyo, Yokohama-shi, Osaka-shi, Singapore and Seoul.

“What that’s saying is that we have cultural preferences for large properties and we, to some extent, pay the price for that,” he says.

I would like a bigger house

I wonder, often, about how much space is in the roof. Can we build an extra bedroom up there? Maybe an en suite bathroom? Could we open up the third bedroom and make a big open living space? Maybe we can squeeze a tiny studio in the garden. Because while this is enough for now, we are constantly thinking: how will this work when the children are grown?

Half of all 18-29-year-olds live in their parental home. The housing affordability crisis has created its own ouroboros – the homeowner’s impetus to make their house as expensive as possible effectively prices out the children who have grown up in these houses from affording their own. And so houses now may need to be bigger to accommodate the greater number of larger bodies that inhabit them.

“The need for separation is greater when you’ve got semi-autonomous young adults living under the same roof as their parents,” says Pawson.

“Older teenagers and adults are not leaving home,” says Lewi. “People who might have downsized at a younger age are now feeling like they have to support their adult children, so they need larger houses.”

Lewi has two sons, 17 and 22. “They’re both living at home and will never leave. One of them lives in a cabin in the garden,” she laughs. The cabin was originally designed to be a home office, and place for guests. Separate living quarters, like cabins, real estate agents have told her, are now a huge selling point.

Is there a way back from big house culture?

Lewi suggests that large houses that are far away from facilities are “really bad for ageing populations”. Wheeler imagines that large homes with long commutes from the city may become “stranded assets”. A shift to denser, smaller living is firstly and mostly a financial necessity for many, he argues, not a cultural or philosophical rejection of expansive private domains. “The market will dictate,” he says.

“People are living in apartments, exploring more densification, through necessity,” says Lewi. “And they’re finding, perhaps, that’s bringing them more community.”

“We been moving away – maybe quite slowly – from the suburban home ownership dream,” says Pawson.

After decades of ever-expanding houses, we may have reached a kind of breakpoint. Where for a new generation, the Australian promise of a big house, the myth of the quarter-acre block has moved so far away on the horizon, they see it not as a dream, but a mirage. Which is, in no small way, quite big.

∎