In an early episode from the first series of The Simpsons, Homer is seen reading a publication called The Bowl Earth Catalog. It’s a punning nod to the Whole Earth Catalog: the 1960s counterculture tome of west coast environmentalism, DIY and tech utopianism (and more quietly, consumerism) that was championed by Steve Jobs and Silicon Valley mavens. It’s a typical blink-and-you’ll-miss-it reference for those who want to see it, but offers a glimpse at the prehistory of The Simpsons.

By the time the show’s creator, Matt Groening, was making it as a cartoonist and comic strip artist in early-80s LA, the hippy counterculture was ageing out (and getting rich). The baton had been passed on – or grabbed – by the burgeoning alternative culture of punk and new wave music, with weekly alt-newspapers, self-published zines, underground comics and much else in between. Whatever you labelled it, a DIY ethos remained ever-present.

It all seems a far cry from the behemoth The Simpsons became: from its early merch-filled Bart-mania period to its imperial 90s era, and on into two further decades including a film and a continued run of record-breaking shows.

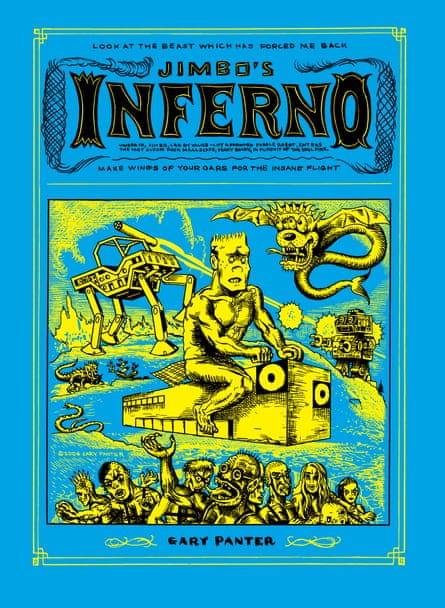

On YouTube, a video hints at early, scrappier foundations: in it Matt Groening introduces his friend, the artist Gary Panter, at a bookshop event in LA in 2008. He quotes from the Rozz Tox Manifesto, a set of 18 commandments Panter had published in 1980: “This is item 12,” Groening reads, listing his favourites. “‘Waiting for art talent scouts? There are no art talent scouts. Face it, no one will seek you out, no one gives a shit.’ Item 15. ‘Law: if you want better media, go make it.’”

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

“We sure were interested in getting our work out,” Panter says over the phone from his home in Texas. “We both wanted to invade media.”

Panter, a painter, illustrator, musician, and more recently maker of bracelets, originally published his satirical manifesto piecemeal in the free personals section of the Los Angeles Reader, an alt-weekly that launched in 1978. It was a call to arms of sorts, mixing the avant garde and low culture, the outsiders and the mainstream, to make something new within the prevailing system. There was a small pool of like-minded people circling. “It was art students mostly, and ugly nerd kids and fat kids, and so that was kind of great,” Panter recalls.

Around the same time, Groening, then an aspiring comic artist who had moved to LA from the Pacific Northwest, started self-publishing his Life in Hell comic strip, a series of darkly funny observations featuring anthropomorphic rabbits, while working at a branch of Licorice Pizza record shop (later memorialised by Paul Thomas Anderson’s 2021 film). Life in Hell was “really smart, very minimal”, says Panter, who wrote Groening a fan letter. “We met at a party. And it turned out we were both Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart fans. And so we just hit it off and started hanging out. We were both broke. So we would pool our resources and share hamburgers and stuff.”

Groening and Panter collaborated on comics for punk zines under names including the Fuk Boys. Byron Werner (who went on to a long career in Hollywood visual effects) was also among their LA set, self-publishing comics, while the influential cartoonist Linda Barry was a friend of Groening’s, “so out of that came this giant explosion of mini comics across the country in the next few years. There was a lot percolating at the same time,” Panter says.

People were not used to seeing that type of humour on TV. Most comedies were extremely blandBill Oakley

Groening continued with his weekly Life in Hell strip, eventually syndicated widely in alternative papers – and, improbably, he kept it going until 2012 despite his vast television commitments. One of Panter’s signature antihero characters, Jimbo, complete with spiky hairdo, is credited by many, including Groening, as an inspiration for Bart Simpson. “He’s said that. I think he’s being kind,” Panter demurs.

Panter was the first to attain greater mainstream success, entering television in 1986 to design surreal, Day-Glo sets for Pee-wee’s Playhouse, though he left after three years feeling burnt out by the experience. “Matt was much more equipped to function [in the mainstream]. I really just wanted to be a painter, or a cartoonist, which is what I did. Matt was a class president, explorer, boy scout, football star. We both had dads who drove us crazy – so we wanted to prove ourselves, I guess.”

Groening would soon follow Panter into television, when the under-heralded producer, production designer and writer Polly Platt gave director-producer James L Brooks an original Life in Hell artwork. Brooks, who was involved in everything from The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Taxi to Broadcast News, helped Groening go from underground comic strip to bratty TV sketches, then world-renowned sitcom.

What was unusual at the time was that the sensibility of The Simpsons found its way into primetime TV, melding Groening’s alternative cartoon underpinning with more offbeat and cynical late-night comedy writers, hired from Saturday Night Live and David Letterman.

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

“People were not used to seeing that type of humour on primetime TV. It’s hard to believe now,” says Bill Oakley, who along with writing partner Josh Weinstein, joined the hallowed Simpsons writing room in 1992. “Almost 70% of TV probably has that sensibility today. But at the time most comedies were extremely down the middle, extremely bland.”

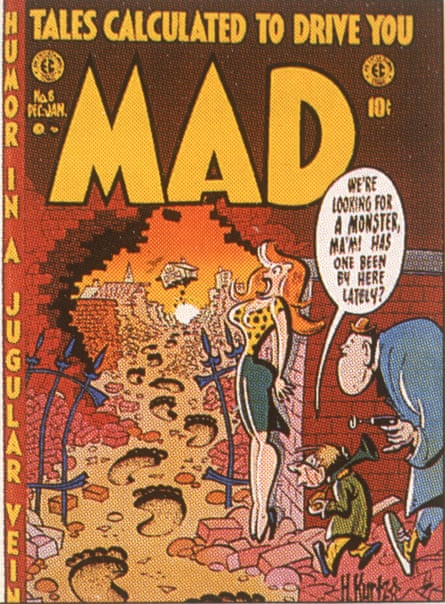

The competition at the time was more safe sitcoms such as The Cosby Show and Mad About You, but The Simpsons was looking further afield. Mad magazine was an obvious childhood favourite of all the writers, says Oakley, while Fox’s Married … With Children was an irreverent sitcom antecedent. Another touchstone, less widely known in the UK, was the 1960s sitcom Green Acres, about a fish-out-of-water New York couple. Its daring and willingness to break the fourth wall was the sort of humour that could have easily sat with The Simpsons.

The related National Lampoon and Harvard Lampoon magazines were the other natural threads. While the former set the alternative comedy template taken up by SNL, the latter was a more direct breeding ground for many writers. The majority of the early Simpsons writers’ room, Oakley included, went to Harvard and wrote for the Harvard Lampoon – a lineage so prevalent at The Simpsons, it became a source of some eye-rolling. “By the late 90s you weren’t talking about your Harvard Lampoon affiliation very much,” Oakley says. “Other people got sick of hearing about it. The thing about the Lampoon, though, is not just the sensibility; it’s like going to graduate school in comedy.”

View image in fullscreen

View image in fullscreen

George Meyer was one of those who came through the Harvard Lampoon line. After college he wrote for then upstart late night chatshow host David Letterman, among other things, and on the side self-published a small humour magazine called Army Man (“America’s only magazine,” ran the tagline). It featured work from Meyer himself and future Simpsons writers including John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti and Ian Maxtone-Graham, as well as cartoonist Roz Chast and comic actor Bob Odenkirk.

Although it only lasted three issues, its influence went far: copies of copies were passed around on college campuses, while offers to expand the publication and turn it into a TV show came in. Among its fans was Sam Simon, the writer-producer who was putting together the team for The Simpsons and recruited Meyer and other Army Man contributors. The little magazine had an outsized impact on The Simpsons’ comic foundations. There is also neat parallel and connective tissue between these self-published humour magazines (Oakley and Weinsten briefly had their own, too), and the alt-zines and comics that Groening and Panter had experimented with years before.

The writers were young but had experience. They’d written on Garry Shandling, Tracey Ullman; they were top young mindsJohn Ortved

By the 2000s Meyer, gentle and hippy-ish in outlook, was a richly garlanded executive producer. “The funniest man behind the funniest show on TV,” was how the New Yorker characterised him in a 2000 profile. Equally celebrated is Swartzwelder, one of the original writers, who is credited with the most episodes in the show’s history, as well as some of its most beloved jokes and characters infused with a sort of carnivalesque, cracked Americana. Reclusive and rarely photographed, Swartzwelder, who left the show in 2003, has an almost mythic reputation among Simpsons fans and serious comedy watchers. “He was a totally unique unicorn, who came from an entirely different universe,” says Oakley.

Such characters can lead one to believe that The Simpsons was a haven of Zappa-infused, Pynchonian oddballs. However, John Ortved, author of The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorised History, undercuts the mythologising a little – even Swartzwelder, for all his eccentricities, previously worked in advertising. The writers’ room was ultimately made up of “professionalised TV writers, led by Sam Simon”, explains Ortved. “He’d written on Taxi, he’d written on Cheers. It didn’t come more establishment than Sam Simon. And the writing room he put together, it wasn’t all grizzled veterans like him, it was a very young room but they had experience. They’d written on It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, Tracey Ullman, these weren’t fresh-faced youngsters with an axe to grind; these were the top young minds in the industry.”

Ortved points out that what made The Simpsons particularly special was this mix: the nerdy Harvard guys, the professional TV writers, Groening’s cynical gen X outlook, and all of it shepherded to screen by Hollywood veterans Brooks and Simon. Also key was that the Fox network largely gave The Simpsons a free hand to produce what they liked. It was the very collision of art and commerce that the Rozz Tox Manifesto had jokingly demanded a decade earlier: “An avant garde placed squarely in the entertainment field …. Capitalism for good or ill is the river in which we sink or swim.”

There is a poignancy here, too. It seems ever harder to imagine such a perfect storm of talent could brew to create a show with the impact of The Simpsons today. As last year’s Hollywood writers’ strike showed, the conditions and opportunities for creative people continue to worsen. Meanwhile the wider landscape has also got tougher: the alt-weeklies that helped people find their voice have fallen off, and zines are largely a relic of a pre-internet time.

Gary Panter sometimes wonders if the underground can still exist in the age of the internet shining a half-light on anything and everything – but then remains defiant. “There still is an underground,” he says. “That’s the great thing. People are not necessarily trying to be underground but there are tens of thousands of creative people doing stuff, who aren’t just looking at the biggest projects.”

Panter says that when Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly started Raw magazine in 1980, showcasing alternative comics, there were very few American artists working in the medium that they were interested in, but now there are thousands. And there’s no need to over-sentimentalise particular past moments. The culture thrives out there regardless.

“People are like: ‘Oh, what was the LA punk rock scene like?’” he says. “LA punk rock was like any time you go out in the middle of the night to a club to see what’s gonna happen. That’s what it was like. And it’s still scattered all across the country and the world.”

The Simpsons is available on Disney+.

∎